Five Queer History References in POSE You Might Have Missed.

Some of the historic show's most memorable events actually happened.

This weekend, fans will say goodbye to POSE—the landmark FX series that brought the glamour, heartbreak, and grit of New York ball culture into millions of living rooms across the country.

With its stories of Queer chosen families—particularly among Black and Brown trans people—and the unprecedented trans representation both behind and in front of the camera, POSE proved that audiences are more than eager to see stories that have too long gone unrepresented.

Throughout its three seasons, POSE used historical fiction to embody the essential truths of its real life sources. In doing so, it offered its own spin on actual events in Queer history, bringing even more visibility to the community’s formerly forgotten stories.

Here are some of the times POSE drew from real life events to create art.

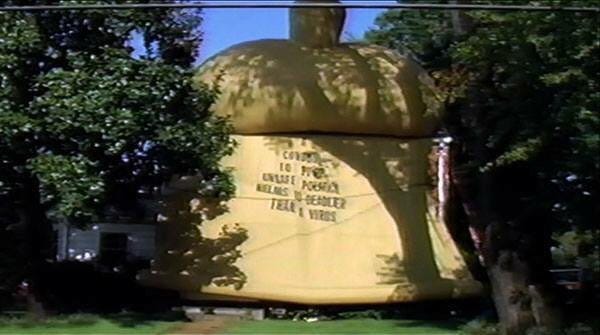

The giant condom.

Blow, the seventh episode of the show’s second season, featured the culmination of protagonist Blanca Evangelista’s battle with her cruel landlord, Frederica Norman.

In an act of defiance—as well as a PSA promoting safe sex during the AIDS epidemic—the House of Evangelista, with help from Elektra Abundance, inflates a giant rubber condom and drapes it over Frederica’s home.

This was a direct allusion to one of the most memorable direct action protests (known as “Zaps”) from the Treatment Action Group (TAG), then a subgroup of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP.

Throughout the epidemic, Republican Senator and virulent homophobe Jesse Helms railed against the provision of funding for HIV/AIDS research. His disdain for people with AIDS made Ronald Reagan look like Tammy Faye.

Helms once said “it’s their deliberate, disgusting, revolting conduct that is responsible for the disease.”

Another time, he called for no intervention against the AIDS epidemic because he there was “not one single case of AIDS in this country that cannot be traced in origin to sodomy.”

Helms’ influence led to discriminatory laws that barred people with AIDS from traveling to the United States and prevented the CDC from spending federal funds on initiatives to combat the disease.

Veteran ACT UP member Peter Staley wrote in a 2008 article:

Our country never launched a single well-funded HIV prevention campaign because of Jesse Helms.

But ACT UP made its opposition to Helms clear—and they went to his house to do so.

The group tracked down Helms’ address with the help of what Staley called a “gay spy” in the Hart Senate Office Building.

After getting specs on the Helms house and securing a large sum from an anonymous donor, ACT UP contacted the media and showed up to the (empty) home.

With a task assigned to each person, the condom was already draped over the house and its reservoir nipple inflating before the first cop car even arrived.

Printed on it were the words:

A CONDOM TO STOP UNSAFE POLITICS. HELMS IS DEADLIER THAN A VIRUS.

Years later, it was revealed the “generous donor” of the funds to make the condom was none other than business magnate David Geffen.

The Die-in at St. Patrick’s.

In 1989, two years before the condom zap, ACT UP launched its most controversial protest during mass at the landmark St. Patrick’s Cathedral—a moment that was also embodied in POSE.

In the first episode of POSE’s second season, Pray Tell enlists House of Evangelista members to join ACT UP in a protest at the cathedral. After sitting in the pews til the service is underway, they walk to the center aisle and collapse en masse in mass.

This was based on an ACT UP die-in at St. Patrick’s in December of 1989.

Die-ins were one of the group’s signature zaps. As AIDS deaths continued to skyrocket, die-ins forced people to do what ACT UP felt they were doing already: ignoring piles of dead bodies, stepping over them, trying to proceed like everything was normal.

At that time, American AIDS deaths were nearing 100 thousand and the rate was increasing rapidly. The Vatican held a conference on AIDS in November of 1989 to address the dissonance between protecting believers from AIDS and the Church’s teachings on contraception and abstinence.

Opening the conference was John Cardinal O'Connor of New York, who railed against condoms—a key method of slowing the spread of the virus (sound familiar?).

O’Connor said:

The truth is not in condoms or clean needles. These are lies, lies perpetrated often for political reasons on the part of public officials.

Fully grasping that unprotected sex could be deadly in the face of the epidemic, ACT UP organized the Stop the Church protest the month after O’Connor’s comments.

In addition to a 4000-person demonstration outside, a number of protestors infiltrated the cathedral for Sunday Mass, where—as seen in POSE—they collapsed in the center aisle, demanding the church stop murdering with misinformation.

What wasn’t included in POSE was the action by one rogue member who destroyed a consecrated communion wafer in the heat of the moment. The outrage prompted by the destruction of the wafer—which Catholicism teaches is the transmutated body of Christ when consecrated—nearly overshadowed the entire demonstration in the days that followed.

Over 100 ACT UP members were arrested that day. Many of them refused to move. Police handcuffed them and carried them out on gurneys.

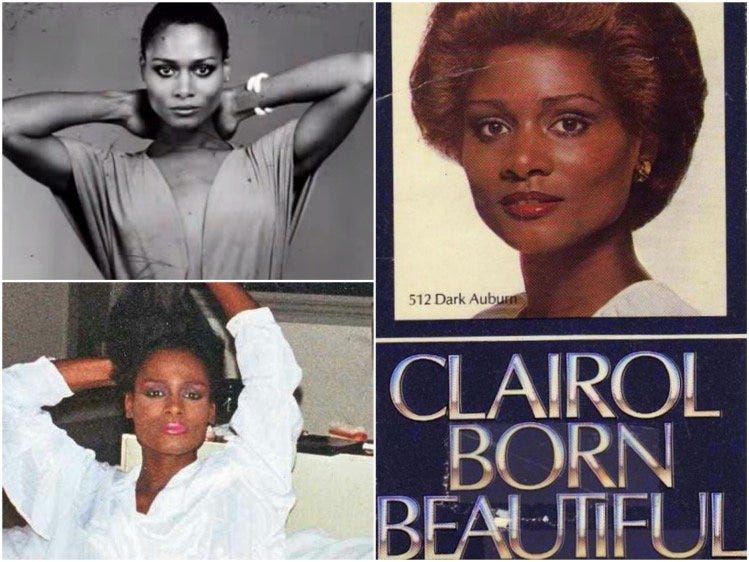

Tracey Africa Norman.

One of POSE’s main arcs features Angel Evangelista’s efforts to break into the modeling world.

From the start, her career shows promise. She places in the top 10 of a Ford Models contest, lands an agent, and soon secures a deal as the face of Wet n’ Wild Cosmetics.

Her career derails when a predatory photographer outs her assigned sex, and—until later in the season—the work dries up.

POSE producer, writer, and director Janet Mock has confirmed this was in reference to the career of Tracey Africa Norman.

After transitioning in the 1970s, Tracey—like Angel—was forced to conceal her assigned sex in order to book reliable modeling work.

Her career took off. She booked campaigns with Avon and Italian Vogue. The legendary model Pat Cleveland said of her, “She looked like how the girl next door might wish to look.”

Her biggest campaign was for Clairol: Born Beautiful hair color. Tracey’s contract was renewed twice by the company and she was told that 512 Dark Auburn—her color—was the hottest selling box.

But in a 1980 shoot for Essence, she was outed as trans by a hairdresser who then told the editor. According to Tracey, the shoot suddenly stopped, as did much of her modeling opportunities shortly after.

For decades, Tracey struggled with poverty but found solace in walking the balls with the House of Africa, eventually becoming its Mother and using her experience in the modeling world to teach her children to walk on air.

After a riveting in-depth profile for The Cut in 2015 by Jada Yuan and Aaron Wong (whose contents were a godsend for this article), Tracey’s story became widely known.

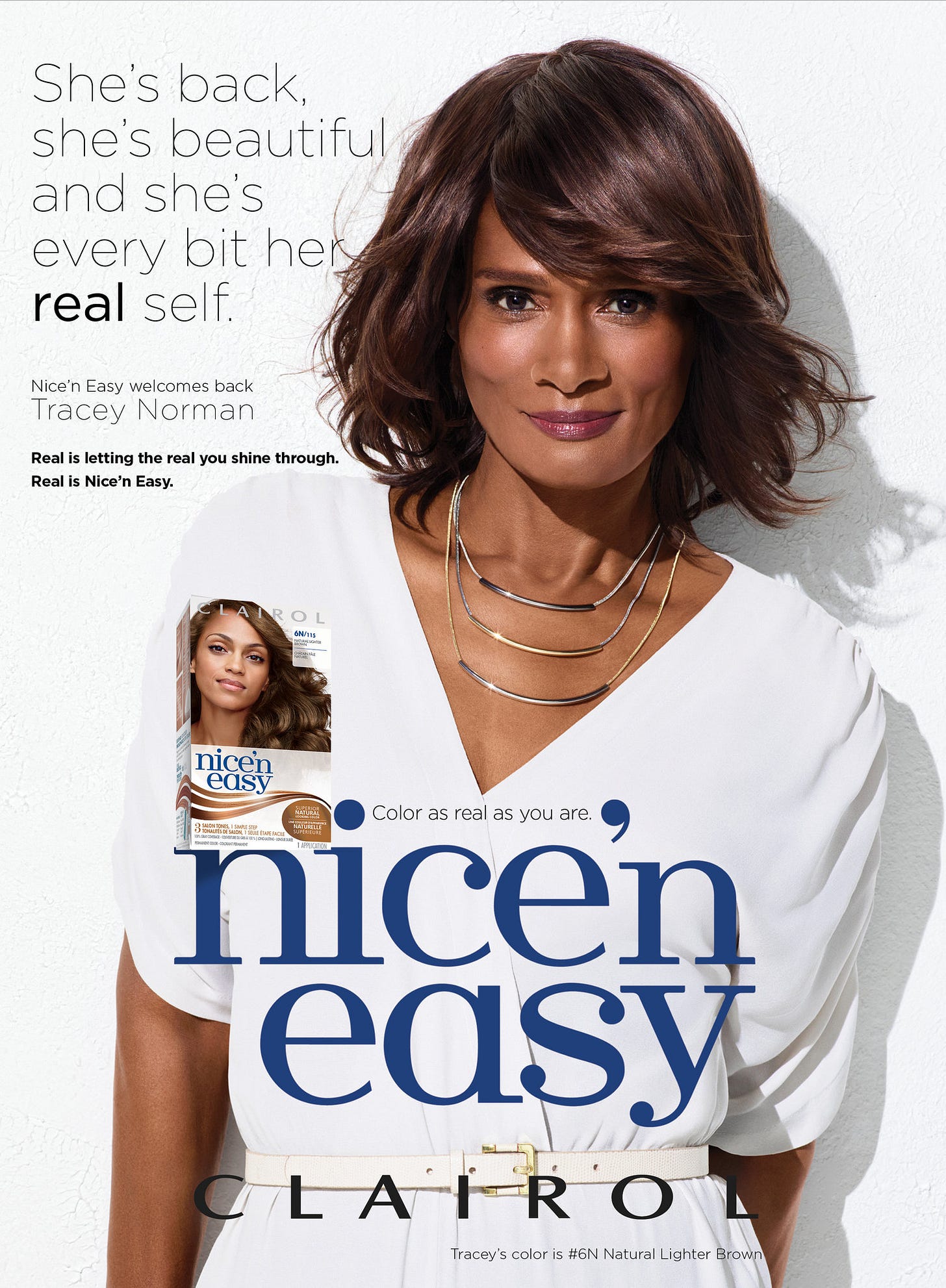

Clairol reached out after the piece was published and hired her to be the face of its Nice 'n Easy Color As Real As You Are campaign.

Before a year was up, Tracey was on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar with fellow trans model Geena Rocero. Let’s hope we see a similar happy ending for Angel.

(I cannot stress enough that the profile in The Cut is required reading)

The trunk.

Yes, that trunk.

In the show’s second season Elektra Abundance Evangelista is working as a dominatrix when one of her clients overdoses. Knowing how the cops will treat a Black trans woman reporting a dead body, Elektra decides to hide it out of self-preservation.

With the help of her children, she coats the body in lye and stuffs it into a large trunk, which she then shoves into the back of her closet.

Though we get a heart-wrenching back story on the trunk in the show’s third season (which I won’t spoil for you), little is known for certain about the real life trunk that inspired it.

Dorian Corey was the Mother of the House of Corey and one of the formative mothers of the art of vogue. She was immortalized in the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning, where her distinction between “shade” and “reading” would prove to be a cultural milestone.

Three years after the release of Paris Is Burning, Dorian passed away of AIDS related complications.

After Dorian’s death, her friends went to her apartment to organize her belongings when they made a gruesome discovery: a mummified body hidden in a trunk in Dorian’s closet.

The body would later be identified as Robert Worley’s, though that’s about the only thing we know. The cause of death was an apparent gunshot to the head, and detectives said the body had been in the trunk for over two decades.

It’s believed that Corey killed Worley in self-defense—that he was an attempted burglar or domestic abuser.

The beach.

In the second season’s finale, Elektra, Blanca, Angel, and Lulu take a well-earned vacation to the beach. A welcome respite from the stress of their daily lives, they bask in the sun and relish every luxury available to them. Blanca finds love. Elektra delivers a masterful takedown of a white woman who dares to try and silence her.

It’s a moment of self-actualization for all of them that reminded me of another scene in Paris Is Burning with Brooke and Carmen Xtravaganza.

Brooke relishes the freedom brought by her recent gender confirmation surgery, where she says:

I am as free as the wind that is blowing out on this beach!

It’s an uplifting moment of pure, unabashed joy and authenticity unblemished by the torments of a cruel world.

Brooke and Carmen collapse into laughter before singing the Queer anthem “I Am What I Am” from La Cage Aux Folles.

This is what POSE did. The Queer histories and universes it repurposed to fit within its story—without losing any sense of the Queer spirit that created these historic moments—is what I’ll miss the most.

The series finale of POSE airs Sunday night on FX at 10pm ET.